Ellis Park / Tampawardli (Park 24)

Start at the front of the Adelaide High School (location #1 on the map below).

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people.

1. Introduction and Naming

2. Sport

3. Signals, Post and Telegraph

4. Quarry, rubbish dump

5. Lie of the Land

6. Native vegetation

7. Native apricot tree

8. Centre of the Park

9. Weather observations

10. Emigration Square

11. Bakewell underpass

12. Road realignment; boundary change

13. Former observatory

14. Adelaide High School

15. Mini-forest: former Weather Bureau site

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 2 Mb)

1. Introduction and Naming

This Park is best known as a venue for soccer and cricket. But it has some hidden remnants of rare native vegetation, and is a key part of the Park Lands trail. One of the main features of this trail is discovering what USED to be here and is now long-forgotten.

This trail starts from the front car park of the Adelaide High School on West Terrace. Park 24 is roughly square in shape. It has changed dimensions since the time the Park Lands were first laid out by Colonel Light, but the boundary changes have been relatively minor, to accommodate different road alignments and the railway line.

It’s just over 35 hectares, and is bounded by;

the railway line through Mile End

Sir Donald Bradman Drive

West Terrace; and by

Glover Avenue, which is the continuation of Currie Street

This area has been known as ‘Park 24” since at least the 1890’s if not earlier. For more than 100 years that was the only name that it had – simply Park 24. Then, in 2002, the City Council assigned Kaurna names to all the Parks.

The name Tampawardli means “house on the plain” “Tampa” meaning “plain” and “Wodli” meaning house.

The name recognised that one of the very first uses of this Park in the late 1830’s and the 1840’s was a camping ground for newly arrived migrants.

The English name, Ellis Park, honours Val Bertram Harold Ellis who served as City of Adelaide Director of Parks & Recreation from 1966-83. Starting in 1982, the name Ellis Park was used just for the sporting fields.

In 2017 the City Council approved English language names for all the Parks, and so since 2017 the name “Ellis Park” has been applied not just to the sporting fields but to the whole of the Park.

So now, the full official name is Ellis Park / Tampawardli (Park 24)

From this starting point, walk towards the two-storey sports building located behind Adelaide High School.

Val Ellis plaque in Park 24

2. Sport

.

Several schools, and sporting clubs use the playing fields in Park 24. The main users are teams from Adelaide High School, the Adelaide Comets soccer club, and St Mary’s Catholic college

Back in 2017, the City Council gave approval for a proposed new building that was described (at the time) as: “incorporating an under croft or similar design solution that minimises visual impact on the Park Lands.” The concept of an undercroft was not carried into practice when this two-storey building went up the following year.

The tenants of this building are the Adelaide Comets Soccer club and the Western Districts Athletics Club. The building was made possible with a $3 million grant from the State Government.

Adelaide Comets soccer club playing in Park 24

Prior to construction of this building, there were two separate but much smaller sheds here: one shed for the Comets and the other for the Athletics Club. Both were demolished in 2019 after the new two-storey building was completed.

Throughout the Adelaide Park Lands, there are more than 30 locations where sporting fields and buildings are leased or licenced from the City Council. The combined area of sporting leases and licences makes up about 13 per cent of the total area of the Park Lands.

More than 20 different sports are played in the Adelaide Park Lands, generating an estimated 1.7 million visits by sports players and officials. That’s about 20 per cent of all Park Lands visits.

There is controversy about buildings of this size on the Park Lands, and especially when buildings such as this one incorporate private function centres. Tension has been growing during the 2020s, between the demands of elite-grade sport and public access to Open, Green, Public Park Lands. That tension was explored in this 5-minute documentary by Patrick Prior:

When popular matches are played here, it is common to see dozens (if not hundreds) of cars parked, apparently illegally, here on Park 24.

A game day, Sunday 18 February 2024: No parking infringement notices were issued.

There was controversy in early 2024 when the Adelaide Comets won approval from the City Council to erect a permanent fence around the main soccer field here. The club had received State Government funding for the fence, and other building improvements, to allow professional Premier-league matches to be played here.

This permanent black fencing, 1.1 metres high, was installed in 2024. Pic: Shane Sody

From this point, walk diagonally (south-east) across the sporting fields towards West Terrace where it intersects with Franklin Street at traffic lights.

3. Signals, Post and Telegraph

Wireless telegraphy - West Terrace c1900 ~ Source: State Library of SA

Here on the Park Lands directly opposite Franklin Street is an important historical site, but there is no historical marker or any evidence of what was on the site. The site was used for communications – and its usage changed, over almost 150 years, as communications technology changed.

As early as 1841 there was a flagpole erected at the site to give the Adelaide business community shipping information. A “flagstaff keeper” would climb a tower, and using a telescope, could see whether a ship had arrived in the Gulf and what sort of ship it was, by observing the flags that the ship was flying.

The flagstaff keeper would then raise certain flags and/or black balls on the flagstaff. If you knew the code, you could be aware of what type of ship had arrived and what, if anything, that meant for your business.

This was called a “signals station”. In addition to the signal tower there was also a flagstaff keeper’s cottage. The system of raising and lowering flags became obsolete after only 15 years. In 1856 the Signals Station was replaced with a telegraph station, which used Morse code, transmitted from the beachside suburb of Grange, where there was a good view of the shipping that was coming up Gulf St Vincent.

An example of a signals station. (Fort Phillip Sydney, 1842) ~ Creator: Sketch by E T Blacket, 1842

In the 20th century, the Commonwealth Government took over posts and telegraphs. The compound here became part of the PMG – the “Post Master General’s” Department. The “telegraph station” as it was then known, included stables, and later (from the 1920s) it was known as the PMG Department’s garage.

In 1956, the PMG’s Department set up operations nearby, in Grote Street. The operation continued there for another 65 years in what was a huge building that spread between Grote Street and Gouger Street. In 2024 the Australia Post building was repurposed to become Kennard’s Self Storage.

But despite its premises across West Terrace, back in 1956, the PMG didn’t want to surrender its building on the Park Lands. Even after the PMG’s department was split up, in the 1970’s, into the separate entities of “Australia Post” and “Telecom” (now Telstra) this land was still burdened with an old metal shed. By that stage it was just called a transport depot. When it was no longer needed as a transport depot, the shed was then reserved for the use of postal and telecommunications employees, as a recreation facility. It was known, by that stage, as the Post-Tel Institute building.

It took until 1987 for the metal shed to be demolished and the site returned to Park Lands. Now there is no record that a signals station or anything else, ever existed here.

From this point walk westwards, about 100 metres into the sporting field.

4. Quarry, rubbish dump

This location used to be a quarry – then a rubbish dump. At this point, like the previous one, there is no evidence of what once existed here.

The practice in the mid-1800s in various parts of your Park Lands was to mine stones, or rubble from various pits – called “Blinding pits”.

In country areas, local governments still do this today. They call them “rubble pits”. Council workers often take rubble, for road building, from private land, with the consent of farmers who are glad to get rid of the rubble.

However, in the Park Lands, in the 1800s, the practice just left large holes scattered around. The holes were then turned into rubbish dumps. This was going on up until at least the 1880s, if not later. Park 24 was affected more than others because this Park had a Council works depot which made it a handy site for extracting rubble.

In 1918, the Council set up a “blinding pit” and works depot or yard on a Part of Park 24 that was not visible from West Terrace. They picked a spot that is now here, in the middle of a soccer field off West Terrace opposite the city block between Waymouth and Franklin Street.

The depot and the blinding pit were hidden from view because of the “signals station” or telegraph station that fronted West Terrace, and also because it was hidden behind a hedge.

The City Gardener of the day, August Pelzer, was keen on kei apple hedges. There are several of these hedges still existing in your Park Lands. They produce a sour yellow fruit, about the size of apricots. In 1918 Mr Pelzer arranged to have planted 140 kei apple trees to form a hedge around this works depot. The hedge gradually grew over and obscured the tall jarrah wooden and barbed wire fence around the Depot.

A kei apple hedge like the one that previously existed in this location.

It appears that the depot lasted less than 20 years because an aerial photo of 1936 shows that it had gone and been replaced by a new works depot off what was then called “Hilton Rd” - what we now call Sir Donald Bradman Drive.

Now both of those depots have been removed.

From this point, walk diagonally, south-west across the sporting field to the next stop alongside Sir Donald Bradman Drive. Stop where you can see a collection of what look like small stone huts.

5. Lie of the Land

The colonisation of Australia effectively dispossessed Aboriginal people who had lived on this continent for tens of thousands of years. In the Adelaide region, the First Nations people are known as the Kaurna people.

There are some general historical references to Kaurna and Aboriginal use of the western Park Lands, including this Park 24. This would have been a camping site before and after European settlement.

In 1844 the “Protector of Aborigines” reported a gathering of Aboriginal clans, associated with what he called “an inter-tribal fight” here in this Park. Three to four hundred were gathered here with what the official said were “weapons for attack”.

The police confiscated and smashed those weapons as part of their intervention.

Aboriginal use of this Park continued for decades after European settlement, right into the late 1800s despite attempts by the colonial Government to prevent encampments.

On both sides of Sir Donald Bradman Drive you can see a collection of dome-like rock structures. This is a public art installation called the ‘Lie of the Land’, opened in 2004.

It was inspired by a drawing in the SA Art Gallery of indigenous Australians camped near Adelaide at the time of European settlement.

Artists Jude Walton and Aleks Danko won a design competition in 2001 to create an entry gateway statement for Adelaide, which would be visible en route from Adelaide Airport to the city.

The total display, on both sides of the road, comprises 25 structures. They are made primarily of stone from Kanmantoo.

From here, walk west along Sir Donald Bradman Drive, turn right and enter the wooded area west of the driveway.

6. Native vegetation

This area is an “open woodland” within Park 24.

In the early decades of European settlement, (the 1840s to the 1860s) the entirety of the Adelaide Park Lands including this Park was stripped of native vegetation. There was a wholesale massacre of trees. They were cut down for construction timber, for fencing, and for firewood.

Then, from the 1870s, there was some recognition that Adelaide needed to do better. Surprisingly, the first step did not involve planting trees (or at least not many trees). For most of the Park Lands, including this one, the first thought was that the Parks needed to be fenced. Therefore, post and wire fences were erected. Most of the eastern and southern Parks were fenced in 1870s. This one was not fenced until the 1890s. The first fence in this Park, in 1890 was around a paddock (on the site of the current Adelaide High School Oval) for the purpose of keeping horses.

There was not much attention given to the western Park Lands any earlier than the 1890s. Throughout most of the 1800s this area was not really treated as if it were a Park. As noted earlier on this Trail, various parts were used as quarries and rubbish dumps. Later it hosted a City Council works depot.

The land was also used for grazing sheep and cattle – because it was convenient to herd the stock from the western Park Lands to the cattle yards, located where the Royal Adelaide Hospital now stands. The City Council also operated a slaughterhouse or abbattoir nearby, on Park 27, where the Bonython Park kiosk stands – only a kilometre from this Park.

Re-vegetation

In 1880, the City Council employed a forestry expert from Scotland, John E Brown who, when he arrived in Adelaide, literally wrote the book on how to re-plant the Adelaide Park Lands.

He was ahead of his time because many of his suggestions from 1880 were not taken up for at least 20 or 30 years, long after he had moved on from Adelaide.

His plan for the western Park Lands was for dense plantings on the perimeter of the Park. This was partly followed through, and this area of open woodland along the railway line to the west, and along Sir Donald Bradman Drive to the south are broadly in accordance with John Brown’s 1880 plan.

This is not the only part of Park 24 that has been re-vegetated. In 2017, dozens of trees were planted just off West Terrace between the High School and Sir Donald Bradman Drive. It seems to be something of an echo of Brown’s 1880 plan.

There is also a small re-vegetation site right on the corner of West Terrace and Glover Avenue, the last stop on this Trail.

From this point, keep following the path until it curves around to the right a little, and then straightens up.

7. Native apricot tree

At this point where the path straightens up to head north, look across to the west, on your left – towards the railway line.

About 10 metres away from the path, you should be able to see five massive logs, old tree trunks, lying in a row on the ground. The old logs are forming a barrier to protect a small tree with multiple slender grey trunks, a weeping appearance and long, slender leaves. This is an unusual specimen.

Most of the trees within the Adelaide Park Lands were planted after European settlement, and chosen by various Adelaide City head gardeners over the years.

However there are some remnant native species that still exist, having survived despite human intervention.

The Latin name for this tree is Pittosporum angustifolium. It has a variety of common names: weeping pittosporum, butterbush, cattle bush, gumbi gumbi, or berrigan. Here in Adelaide it is usually called a native apricot.

The native apricot might be called either a large shrub or a small tree. It grows mostly in inland Australia.

It’s a slow growing plant, usually seen between two and six metres high, though exceptional specimens may exceed ten metres.

It is drought and frost resistant. It can survive in areas with rainfall as low as 150 mm per year. A resilient desert species, individual trees may live for over a hundred years.

This might be the largest Native Apricot tree growing wild anywhere on the Adelaide plains.

From this point, walk northwards and then turn right onto a dirt track. The dirt track runs east-west through the centre of this Park. Walk up the slope, with an embankment on your right, and then stop at the crest, before you get to the fenced tennis courts.

8. Centre of the Park

From this point, you can see two tennis courts, and straight ahead the Adelaide High School. But the site of the High School was first reserved for something very different – military barracks!

In 1849 a law approved 1.6 hectares of the Park for a military barracks, where the Adelaide High School now stands. However, the barracks were never built. Instead the site was re-allocated in 1860 for an Observatory. There is information about the Observatory later on this Trail.

The Federal Government tried again in 1910, for a much larger area of 16 hectares which would have taken up almost half the area of this Park. Although no specific site was earmarked, it would probably have included this central part of Park 24.

The suggestion was not warmly received by the State Government or the City Council, so the Federal Government wisely found another site instead – in Keswick. The Keswick barracks were established in 1912 and became the first substantial Commonwealth building constructed in South Australia.

Cyclocross racing

This central part of Park 24 is also used from time to time for the sport of cyclocross racing. Cyclocross bikes are in-between road bikes and mountain bikes. It’s a “cross” sport like “cross-country” running. It’s shortened sometimes to CX.

Riders use special CX bikes, although they look similar to road bikes. Riders must ride dirt tracks, across grass, along some road and at times carry their bikes over obstacles.

In 2019, riders came from all over Australia to the National Championships conducted here in Park 24.

From this point, head north for about 100 metres until you come to an area fenced in black metal wire.

9. Weather observations

Park 24 has an historical connection with weather observation going back to 1838 – less than two years after Adelaide was founded. But this compound is much more recent, being set up only in 2017. The story about why these instruments are located here is a story with a number of twists and turns.

The first records of rainfall in Adelaide were taken in this Park in 1838, by George Kingston who was the Deputy Surveyor to Colonel William Light.

Later, South Australia’s first meteorologist, Charles Todd took over observations in this Park from 1855. That was five years before he had an Observatory built in this Park. When the Commonwealth Government was formed after federation in 1901, the Commonwealth Government’s new Weather Bureau didn’t have its own building, so it shared space inside the State-run Observatory, on West Terrace.

The first purpose-built Weather Bureau came later, in 1940, right next to the State-run Observatory, on a relatively small site, on the corner of West Terrace and Glover Avenue.

The Weather Bureau on the corner site lasted less than 40 years, from 1940 until 1979.

The Bureau was moved to Kent Town in 1977. However the site in Kent Town also lasted only about 40 years.

The Bureau found that Kent Town was not an ideal location for recording weather data. Urbanisation and obstruction by adjoining buildings made measurements at Kent Town less than optimal.

So, in 2017, the Weather Bureau moved its offices into the City, in King William Street, but set up this recording station here, to feed data into its offices. You could say that in 2017, Adelaide’s official weather recording station returned home - almost to the same place where recordings began in 1838.

The equipment installed behind the fence at this site provides observations of air temperature, wind speed and direction, air pressure, rainfall, and relative humidity. These observations are available on the Bureau’s website at ten-minute intervals. The data meets international observing standards.

Before the Kent Town station was shut down the two observation stations operated in tandem for some time. This was done so the Bureau could compare the data and identify differences in the observations for Park 24 versus Kent Town.

The return of a weather station to the Adelaide Park Lands, since 2017 now allows for comparison of records with a time well before urbanisation, and carbon pollution of the atmosphere.

This site with its long history therefore is of global interest.

From this point walk north about 50 metres and stand on the lower or western oval, just before you get to the centre of the oval.

10. Emigration Square

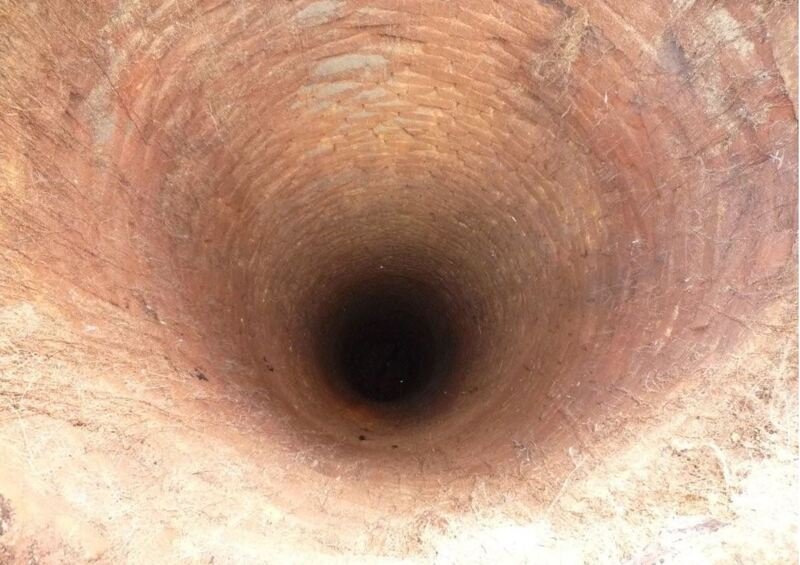

Beneath your feet here on this Park Lands Oval is an historic relic dating from the 1840s.

In 2010 a ride-on mower, operated by a City of Adelaide gardener, hit a small hole on this oval.

The mower driver reported the hole to his supervisor to see whether it needed to be filled in. An investigation was begun, and everyone was amazed at what was found.

Beneath your feet here on the Oval the hole is still there. But it’s not just a hole. It is a very deep brick lined hole. It is 12 metres deep, equivalent to the height of a three-storey building.

The hole is 1.2 metres wide. This is not just a hole - this was an old well.

So what is an old well doing in the middle of the Park Lands? The answer to this question goes back to the very first days of European settlement in Adelaide.

In early 1837, the first settlers had to wait for land to be subdivided and houses to be built. This site was their temporary accommodation. At first they used tents near what is now the site of the Royal Adelaide Hospital. But a year later, in 1838, a dozen or so rough wooden buildings arrived on a ship from England. They were set up here, like a shanty town in what became known as Emigration Square – because they were arranged in a square formation. The primitive shacks were covered in canvas and tarpaulins which were not always adequate to keep out the rain.

This was the first taste of life in the new colony for arriving migrants. The site contained a rudimentary hospital, dispensary, doctor’s quarters in the centre, and of course a well. The well is the only surviving relic of that time.

Within two years (by 1840) the number of rough buildings had increased to about 40. Apart from recent immigrants some of the rough buildings were also commandeered by squatters who had nowhere else to live.

By 1849 the site had been closed for emigrants and for about three years it was used as a women’s destitute asylum.

But by 1852 it had been abandoned. The well was covered up and remained unnoticed in Adelaide for more than 150 years.

After the City Council re-discovered the well in 2010, they invited the SA Museum & Cave Explorers Group to explore it. Some explorers descended into the well and took photos.

The well has been covered over again, and hidden, to remove any risk to people playing sport here.

From this point, walk north-west, towards Glover Avenue, and the railway underpass.

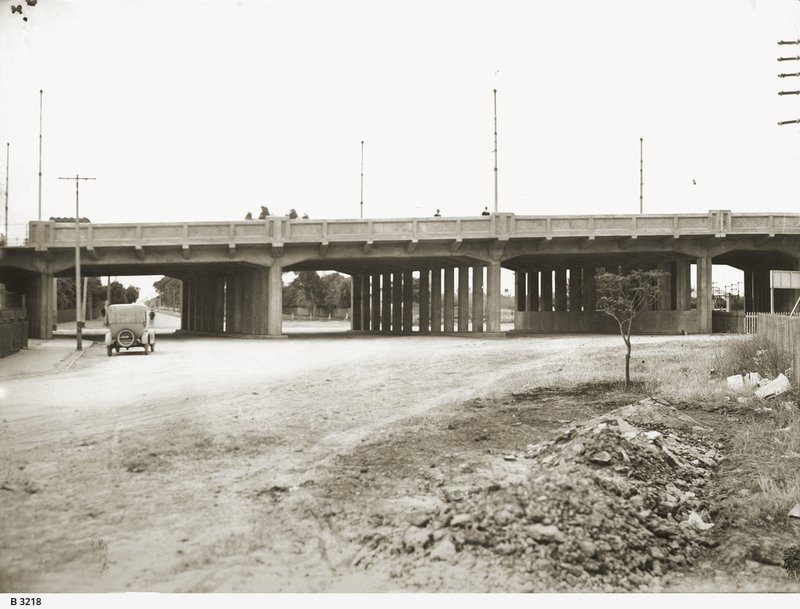

11. Bakewell Underpass

.

This is known as the Bakewell Underpass, which replaced an earlier Bakewell Bridge. For many decades if you were driving from Adelaide to the western suburbs, via Henley Breach Road, you would have crossed over the railway line at Mile End on a road bridge.

A concrete Bakewell Bridge was constructed in the 1920s. It had multiple pylons and the trains went under the road, in-between the pylons. The Bakewell Bridge took all the Glover Avenue road traffic up over the top of the railway line and down the other side to join Henley Beach Road.

In 2001 there was an accident at the bridge. A freight train hit one of the pylons. The bridge didn’t fall, but its structural integrity was compromised. For months the bridge was closed, which created traffic chaos for those who commuted to and from the western suburbs.

The damaged pylon was reinforced as a stop-gap measure, but the State Government immediately started planning to replace the bridge. Eventually the bridge was replaced with what we now call the Bakewell Underpass, constructed in 2006 and 2007, at a cost of $41 million.

William Bakewell who died in 1870 was a solicitor and politician in the early days of South Australia.

From this point, walk back towards West Terrace on the footpath adjoining Glover Avenue. Stop at the point in between the two sporting ovals.

12. Road re-alignment; boundary change

In 1925, there was a change to the size and shape of this Park. This road, Glover Avenue, did not exist before 1925.

Up until 1925, the northern boundary of Park 24 was a different road, to the north of here, called Mile End Road.

Mile End Road was a straight east-west road, that connected Hindley Street at one end, with Henley Beach Rd at the other end.

However, in 1925 Mile End Road was closed, and the new Glover Avenue was opened. (It was named in honour of a former Lord Mayor, Charles Glover). The effect was to make Park 25 (to the north) a little larger and made Park 24 (here) a little smaller.

If you look at a map, you can see that Glover Avenue is not directly east west, but it goes at an angle to connect Currie Street to Henley Beach Rd. The change made Currie Street more important as a thoroughfare, instead of Hindley Street.

The southern boundary of Park 24 is Sir Donald Bradman Drive. Until 2001 it was known as Hilton Road (through the Park Lands) and Burbridge Road (to the west of the Park Lands. Both names (Hilton Road and Burbridge Road) were abolished in 2001 (after Bradman’s death) and changed to Sir Donald Bradman Drive.

Model planes

After the second world war, model aeroplane flying became a popular pastime in Adelaide and elsewhere.

In 1952, the South Australian Associated Aero Modellers were granted permission to fly their planes on the grounds to the rear of Adelaide High School on Sunday afternoons.

There are still 28 different model aircraft clubs throughout SA. Some of them fly regularly in the Park Lands, but not here. One club – for model helicopters – flies in Park 21 and another group (for fixed-wing model aircraft) uses the southern end of Victoria Park. There are signs in those two Parks warning you that you’re in a zone for UAVs. (Unmanned aerial vehicles)

From this point, walk a little further towards the Adelaide High School, and stand on the oval behind the school.

13. Former Observatory

Before the Adelaide High School was on this site, it had a history, for almost a hundred years, as something very different. From 1860 to 1951 on the site of the Adelaide High School there was a large compound with various buildings, together known as the Adelaide Observatory.

An area of 1.6 hectares was set aside in 1861. This was organised by the “Government Astronomer” Charles Todd who until that time had been running the “Observatory” functions from his home in North Adelaide.

This was before Federation so there was no Federal Government, and no Bureau of Meteorology. Mr Todd was basically running the South Australian weather bureau from this site. His work was mainly about the weather and not much about astronomy.

For most of its 90-year life, the Observatory compound comprised a collection of buildings for scientific purposes. They included an “Astronomer’s Residence” as well as what was described as a “Transit Room” and a two-storey “Observatory tower”. There was a telescope and a seismograph, rain gauges, water tanks, sheds. stables, and a garage.

The functions and buildings on the site gradually expanded over the decades. When the Federal Government was formed in 1901 there was a Commonwealth weather station on the site, as well as a State Astronomical section within the same buildings.

Eventually, in 1940, the weather bureau moved out and erected their own building next door, on a much smaller block of land, right on the corner of West Terrace and Glover Avenue.

A few years later, in 1951, the newer Weather Bureau building stayed, but the Observatory was removed – relocated to Adelaide University - to make way for the Adelaide High School

Walk a little closer to the High School, to learn about its history.

14. Adelaide High School

Adelaide High School was established in 1908, but not on this site. It was originally set up on two sites: one in in Grote Street (on the corner of Morphett Street) and the other in Currie Street.

Those two historic school buildings still exist. The one in Currie Street is now the Adelaide Remand Centre. The old building in Grote Street is used as a pre-school. They were the two sites of the Adelaide High School. When it opened in 1908, Adelaide High was the first free high school in Australia. In the 1920’s it was the largest High School in Australia with over 1,000 students.

The idea of putting a campus building on the Park Lands was first raised in the 1930s. At that time, in the early 1930s, a site on Frome Road was approved – in the area between the old Royal Adelaide Hospital and the Botanic Gardens. However, that proved too difficult to arrange so in April 1939 the State Government picked this alternative site on West Terrace; to replace the old Adelaide Observatory.

There was a design competition which attracted 60 entries and the winning design was selected in 1940. However, the disruption caused by the Second World War (from 1939 to 1945) intervened and nothing was done until several years after the war ended.

Firstly, the Observatory was relocated to the Adelaide University, where it was rebuilt in 1948, as part of the Physics building off Kintore Avenue. The Observatory and its telescope remain in use to teach physics students. Only after the Observatory on this site was removed, could work begin to construct this High School. The last of the Observatory buildings were demolished in 1952, while the school was still being finished. Students were enrolled from 1951.

The original cost of the High School, as designed, was supposed to be 60,000 pounds. However, when the construction tender was awarded in 1946 to Baulderstone’s it had blown out to 90,000 pounds.

When the school was first built here, it was exclusively for boys. The girls stayed in Grote Street. In the late 1970s public high schools were “zoned” so fewer boys were eligible to attend Adelaide High. That allowed the Education Department to bring the boys and girls together on this one site, from 1979.

In 2014, this Adelaide High School had a $25-million two-storey expansion, on the southern side.

In 2018, another seven-storey High School was constructed on Park 11 – a Park Lands site next to the Botanic Gardens. There is some irony that the new Botanic High School is very close to the site that as originally picked in the 1930s for this Adelaide High School. The Adelaide High School has been on the State Heritage register since 1985.

In 2019, Adelaide High School was used as a location setting for an Australian TV drama series. “The Hunting” starred Asher Keddie and Richard Roxburgh was a four-part mini-series. It was shown on SBS-TV, debuting from August 2019.

In 2021 the High School was expanded with more extensions at the rear, at a cost of $23 million.

From this point, walk a short way to the north, to Glover Avenue to see the mini-forest next to the High School.

15. Mini-forest: former Weather Bureau site

This small corner block has been reserved for native plant re-vegetation. It has been landscaped to create a small hill on the block, and over recent years, volunteers have been planting native trees here.

The site was returned to Park Lands only in 1979.

From the mid-1800s it had been part of the Observatory, next door.

In 1940 the Commonwealth Weather Bureau (as it was then called) was established here, right on the corner of Glover Avenue and West Terrace. The Weather Bureau was here for 37 years before relocating to Kent Town.

However, during its 37-year life, its next-door neighbour changed dramatically. The old Observatory was knocked down in the period from 1948 to 1952, and the new High School was erected.

The Education Department tried unsuccessfully to take over the weather bureau building on this next-door site, in the hope of expanding the Adelaide High School, but the State Government of the day rejected that bid.

Instead the State Government paid the Commonwealth to vacate the site, so that it could be returned to Park Lands. That occurred in 1979.

There is a plaque on West Terrace, that records the history of the site and its links with the Bureau of Meteorology.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 2 Mb).

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.