by Stewart Sweeney

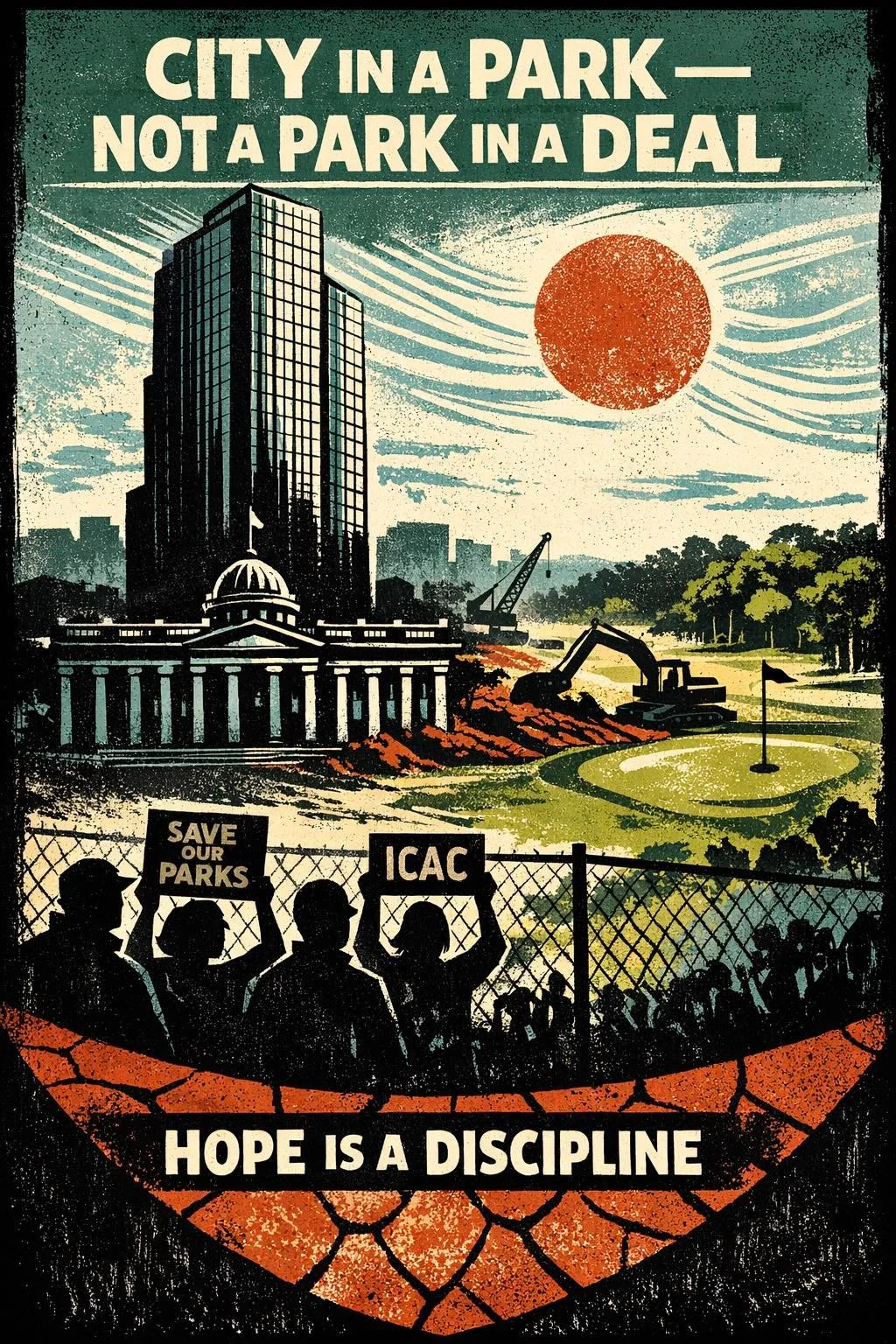

South Australia’s democracy is being hollowed out the modern way.

It’s not a coup. It’s a governing style: smooth power, weak friction, and public space treated as executive territory.

South Australians are not waking to tanks in Victoria Square or a shuttered Parliament. That’s the point. The democratic danger in a prosperous, orderly state like ours doesn’t arrive as a rupture. It arrives as a habit.

A habit of executive convenience. A habit of doing deals first and explaining later. A habit of treating scrutiny as delay, consultation as theatre, and dissent as an operational problem to be managed rather than a democratic signal to be heard.

The result is a democracy that keeps all its rituals—elections, press conferences, “community engagement”—while slowly losing its substance: accountability, contestation, and the genuine sense that citizens can still change the trajectory of power.

“Getting things done” is not the same as governing democratically.

South Australia has, in recent years, embraced a political aesthetic of velocity. Big announcements. Big builds. Big events. Big promises of “delivery”.

Image: Stewart Sweeney/Chat GPT

There is nothing wrong with ambition. But ambition becomes dangerous when it is paired with a governing philosophy that sees democratic friction as an inconvenience. Because friction is not a bug in democracy; it’s the feature that prevents power from becoming lazy, captured, or entitled.

When “delivery” becomes the highest virtue, the temptation is always the same:

Move decisions into tighter circles.

Shorten the time for challenge.

Reframe opposition as “anti-progress”.

Use legislation, fast-track pathways, or special governance structures to run around obstacles.

This is how you get a state that is competent at ‘activation’ but increasingly poor at legitimacy.

Integrity isn’t branding. It’s deterrence. South Australia has lived through a quiet but consequential shift in its integrity settings. The public has been asked to accept a narrower definition of what counts as corruption, a tighter jurisdiction, and a weaker sense that powerful actors should fear consequences for misconduct, maladministration, or influence-peddling.

Whatever the original intent, the lived effect is plain: fewer behaviours trigger the institutional alarm bells, and fewer people in positions of power worry that the alarm bells will ring.

You cannot run a high-trust society on a low-deterrence integrity system.

And even where reforms look strong on paper—such as tighter rules around political donations—integrity doesn’t survive on one reform alone. Money, access and influence simply migrate: into lobbying ecosystems, procurement pipelines, planning negotiations, “stakeholder engagement”, and the soft power of concentrated capital.

If you want democracy to function, you don’t just regulate elections. You harden the everyday machinery of government against capture.

Civic space is shrinking by stealth

A confident democracy treats protest as normal. It may regulate assemblies for safety and order, but it recognises dissent as a form of participation, not a threat.

A nervous democracy does the opposite. It expands police powers, tightens protest rules, raises penalties, and uses “public order” language to reframe civic action as disruption. It insists it is only targeting extremists and troublemakers—while the practical chill spreads to everyone.

South Australians should be asking a simple question whenever new restrictions are proposed: does this expand safety, or does it expand executive convenience?

Because once civic space becomes conditional—something granted by permission rather than protected by principle—the public square stops being ours. It becomes managed space. Public land and planning have become the test case.

If you want to see the modern form of democratic hollowing, don’t start with slogans. Start with planning and public land—because that’s where money, power, culture and identity collide.

When major development decisions reshape the symbolic heart of Adelaide, the issue is not only height, heritage or skyline. It is whether the city is treated as a shared civic inheritance or as an investment surface.

When Park Lands governance is overridden by legislation and state power—when the public estate is carved up to meet the priorities of a global sporting brand—the issue is not whether one likes golf. It is what it tells citizens about who ultimately owns the city.

Planning, in other words, is democracy made concrete. It reveals whose voices count and whose can be ignored.

And here is the danger: once governments learn they can legislate or fast-track their way around resistance—once they discover the public will eventually be worn down—this becomes the template for future incursions.

The lesson citizens receive is corrosive: that engagement is pointless, that outcomes are pre-decided, that politics is a closed loop. Cynicism grows. Trust falls. And into that vacuum comes the illiberal temptation: the idea that “strong leadership” is preferable to “messy democracy”.

South Australia is fertile ground for the wrong politics.

We are a small state with close networks and long memories. That can be a strength—community, cohesion, cooperation.

But it also creates vulnerability: a tighter civic ecosystem is easier to dominate, easier to align, easier to capture. When major institutions—government, property, major events, infrastructure, media narratives—pull in the same direction, dissent can be painted as fringe even when it is broad and serious.

A property-and-event-led political economy has a particular democratic side effect. It encourages governments to treat the city not as a civic project but as a deal pipeline: approvals, precincts, “activation”, land arrangements, partnerships, branding. In that environment, public interest becomes a rhetorical garnish rather than the governing purpose.

What a democratic reset would look like in SA.

South Australia does not need to choose between “getting things done” and democratic legitimacy. It needs to stop pretending the trade-off is unavoidable.

Here is what “different” would look like—practically, institutionally, visibly:

1. A strengthened integrity system with jurisdiction, resources and independence that restore deterrence and public confidence.

2. Radical transparency for major projects: published meeting logs, lobbying disclosures, probity arrangements, value-for-money assessments, and clear conflicts registers—by default, not by FOI attrition.

3. Planning legitimacy reforms that limit fast-tracking and “state significance” pathways to truly exceptional cases, with stronger public reasoning requirements and independent review.

4. A Park Lands governance compact that treats the public estate as a protected commons: no takeovers-by-bill, no “just this once” carve-outs, and a strong presumption against irreversible loss.

5. Civic space protections that recognise protest as democratic infrastructure, balancing safety with rights—and resisting punitive overreach.

6. A culture shift in leadership: less “announce and defend”, more “reason and persuade”; less branding, more accountability; less managing dissent, more listening to it.

The central point is this: democracy needs friction. It needs constraints. It needs institutions that can say “no” to power without fear or favour. And it needs citizens who believe their participation matters—because, in practice, it does.

South Australia can still be a reform state again. But not if we confuse action with legitimacy, or if we keep shrinking the public realm—our parks, our streets, our civic institutions—into executive territory.

A democracy is not only the right to vote every few years. It is the right to shape the place you live, to challenge power without punishment, and to trust that public decisions are made for public reasons.

If we lose that, we will still have elections.

We just won’t have democracy.

The author of this article, Stewart Sweeney, is a long-term member of the Adelaide Park Lands Association.